Filming A Woman of Paris

A Woman of Paris was a courageous step in the career of Charles Chaplin. After seventy films in which he himself had appeared in every scene, he now directed a picture in which he merely walked on for a few seconds as an unbilled and unrecognisable extra - a porter at a railroad station. Until this time, every film had been a comedy. A Woman of Paris was a romantic drama.

This was not a sudden impulse. For a long time Chaplin had wanted to try his hand at directing a serious film. In the end, the inspiration for A Woman of Paris came from three women. First was Edna Purviance, who had been his ideal partner in more than 35 films. Now, though, he felt that Edna was growing too mature for comedy, and decided to make a film that would launch her on a new career as a dramatic actress.

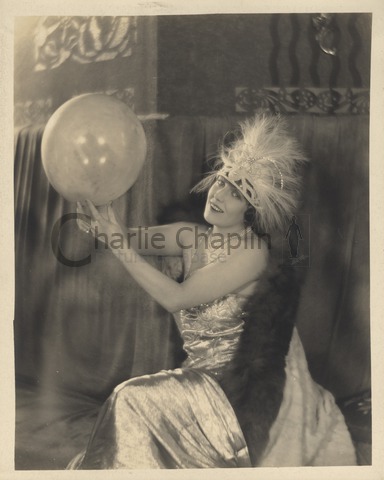

At this moment his life was invaded by the second of the women, Peggy Hopkins Joyce. Peggy was not A Woman of Paris but a barber’s daughter from Virginia. She was however very pretty, and had made a profitable career of marrying and divorcing millionaires. No doubt she now intended to add Chaplin to her list of rich conquests. Instead, it was Chaplin who profited from Peggy. He was fascinated by her colourful stories - how she had been the mistress of a rich Parisian publisher, and how a young man had killed himself for love of her. He listened and stored up the stories - and Peggy and her love life were transformed into the character of Marie St Clair, Chaplin’s woman of Paris.

The third inspiration for the film was the glamorous and temperamental Polish-born actress Pola Negri, who had just arrived in Hollywood. Very soon Charlie and Pola embarked on a tempestuous love affair, which was gleefully reported, with all its dramatic ups and downs, by the world’s press. Two things about this affair with Pola were exceptional in Chaplin’s life. The first was that the affair became so public - though ordinarily he was at pains to keep his private life out of the news. The second peculiarity of the affair was that this was the only occasion on which Chaplin permitted himself to mix work and private life. Normally when he was making a film he had time and thought for nothing else, and certainly not for romance.

But the Pola affair was different. It coincided exactly with the production of A Woman of Paris Charlie and Pola met when Chaplin was in the final stages of preparation for the film, and separated for good three days after he had completed shooting. With such perfect timing, it is tempting to speculate whether this was a real love affair; or whether - however unconsciously - Chaplin was seeking in Pola the model he needed for the kind of sophisticated woman of the world who was hard to find in Hollywood.

At first sight the story might seem like conventional melodrama. Look again and you see how Chaplin has overturned all the stereotypes of the time. The heroine is frankly a courtesan. The hero is a mother-dominated weakling. The bad guy, on the contrary, is charming, considerate and amusing. Hollywood at that time revered mothers and fathers, but here the parents are bigoted and selfish and the cause of all the tragedy.

With A Woman of Paris Chaplin inaugurated a whole new style of comedy of manners, and new styles of acting to suit it. Chaplin’s own genius as a comic actor lay in his observation of human behaviour. Now he applied his discoveries to serious drama - exploring ways of revealing the inner workings of his characters’ hearts and minds through their external actions and expressions.

He found ideal interpreters for his ideas in the brilliant Adolphe Menjou and in Edna Purviance, with her long experience of interpreting Chaplin’s ideas. They play their roles with miraculous subtlety, and an understatement that was unprecedented at this time. Chaplin made a profound comment on his discoveries and on the whole art of the best screen acting: “As I have noticed …, men and women try to hide their emotions rather than to try and express them. And that is the method I have pursued … to become as realistic as possible”.

The press was ecstatic. Neither Chaplin nor anyone else had ever received such unanimous praise for a film. But alas the audience did not share the enthusiasm of the critics. Never had a Chaplin film done such bad business. It seemed that people were not prepared to pay their cents to see a film in which their idol did not appear. Few even recognised him in his bit part as the porter - though these few seconds were a high spot wherever the film was shown.

At the very end of his life, Chaplin tried again with the film. At 86 years old, aided by the arranger Eric James, he created and recorded a new musical score. It was to be mark his last days in a film studio and the final work in an astonishing creative life that had spanned eight decades. Perhaps too it was a kind of reconciliation with a film which the public had rejected, though he himself remained intensely and justifiably proud of it.

Text by David Robinson / Copyright 2004 MK2 SA