Filming The Great Dictator

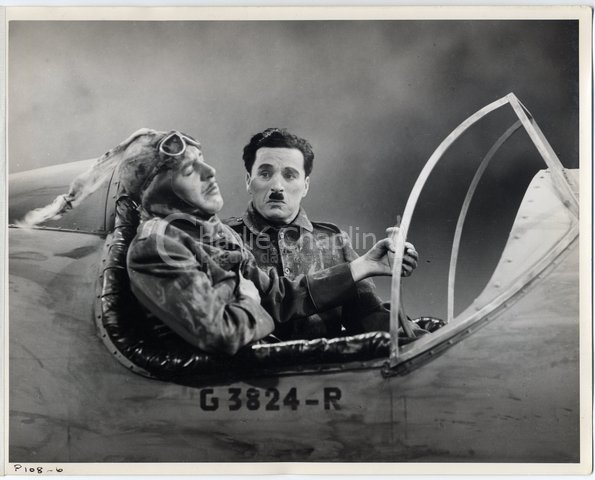

In the autumn of 1938, when the Munich Agreement was being signed in Europe, Charles Chapin was putting the finishing touches to the first draft of a script written in the greatest secrecy. Rumour had it that the creator of the Tramp had decided to make his first talking film. Moreover, it was said that he would be playing the part of a character inspired by Adolf Hitler.

Finally, after the long and painstaking process of revising and then directing, Chaplin presented The Great Dictator in New York on October 15th 1940. The historical circumstances in which he had found himself during those two years were quite extraordinary. His native country, England, had declared war at the beginning of September 1939, but the United States, where he had been living as a permanent resident – but British citizen – since 1913, had resolved to keep out of the conflict that was to bathe the Old Continent in blood.

By waging war against Hitler via the silver screen, Chaplin was making a personal commitment and, albeit with more gravitas, repeating the experience of Shoulder Arms. Even before shooting began, The Great Dictator had enraged German and British diplomats posted in the United States and brought Chaplin to the forefront of celebrities harassed by the House of Un-American Activities.

This struggle in favour of a democratic idea of peace is in itself reason enough for the historian’s interest. Chaplin, however, added to the credits of The Great Dictator the following warning; “Any resemblance between Hynkel the Dictator and the Jewish barber is purely coincidental.” This was a playful way of hinting that what was really at stake was not so much Chaplin’s double role but the tension between him and his twin, the Tramp. Up to now the Little Tramp had conveyed an experience of the world through the language of pantomime, and because he embodied no national identity and spoke no mother tongue, he had touched the hearts of spectators everywhere. His immense success rested on popular acclaim but also on the recognition of intellectuals, especially in France in the 1920s, where many artists and authors praised his genius.

Getting Charlie to speak also meant putting to death this character that had made his creator famous and taking the risk of exposing himself without a mask. Does the declamatory speech at the end of The Great Dictator betray Chaplin’s inability to sustain the aesthetic and comic register all the way through to the end of the film? Chaplin was well aware of these issues, which is why he wrote the words “First picture in which the story is bigger than the Little Tramp.”

Chaplin’s real history was not just the one he was facing up to, but also the one he was recounting by combining the characters of the Tramp and the Jewish barber in the image of the “pariah”.

Copyright © Christian Delage, Chaplin Facing History, published by Jean-Michel Place 2005