Filming The Gold Rush

Introduction

Charles Chaplin made The Gold Rush out of the most unlikely sources for comedy. The first idea came to him when he was viewing some stereoscope pictures of the 1896 Klondike gold rush, and was particularly struck by the image of an endless line of prospectors snaking up the Chilkoot Pass, the gateway to the gold fields. At the same time he happened to read a book about the Donner Party Disaster of 1846, when a party of immigrants, snowbound in the Sierra Nevada, were reduced to eating their own moccasins and the corpses of their dead comrades.

Chaplin - proving his belief that tragedy and ridicule are never far apart - set out to transform these tales of privation and horror into a comedy. He decided that his familiar tramp figure should become a gold prospector, joining the mass of brave optimists to face all the hazards of cold, starvation, solitude, and the occasional incursion of a grizzly bear.

The idea took shape much more quickly than was usual for Chaplin: this was the only one of his great silent comedies which he began to shoot with the story fully worked out. Only two months after the premiere of his previous film, A Woman of Paris he had already sent a scenario (provisionally titled The Lucky Strike) for copyright, and set his studio to work on building sets. Perhaps his activity was stimulated by the public’s disappointment with A Woman of Paris a dramatic film in which Chaplin himself appeared only fleetingly, as an extra.

Complications with Lita Grey

Chaplin generally strove to separate his work from his private life; but in this case the two became inextricably and painfully mixed. Searching for a new leading lady, he rediscovered Lillita MacMurray, whom he had employed, as a pretty 12-year-old, in The Kid. Still not yet sixteen, Lillita was put under contract and re-named Lita Grey. Chaplin quickly embarked on a clandestine affair with her; and when the film was six months into shooting, Lita discovered she was pregnant. Chaplin found himself forced into a marriage which brought misery to both partners, though it produced two sons, Charles Jr and Sydney Chaplin.

As a result of these events, the production was shut down for three months. Lita was replaced on the film by an enchanting new leading lady, Georgia Hale. Georgia, then 24, had arrived in Hollywood after winning a beauty contest in Chicago and worked as an extra until Josef von Sternberg cast her In his shoe-string debut film, The Salvation Hunters. Chaplin screened the film in his home, and instantly decided on Georgia, with her distinctive, delicate beauty, as his new leading lady.

The Shooting and Special Effects

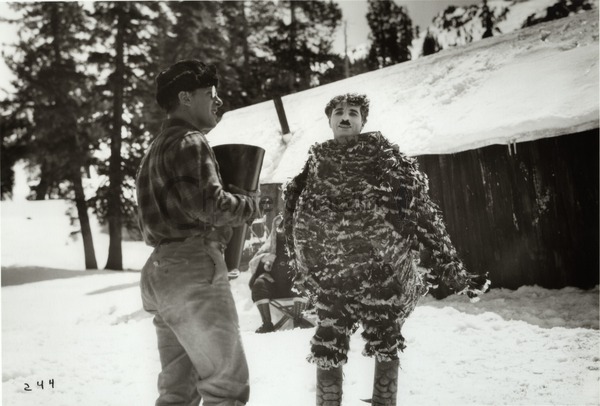

With this unforeseen interruption and the distractions of the Chaplins’ domestic tribulations, the production dragged on for almost a year and a half. It was in every respect the most elaborate undertaking of Chaplin¹s career. For two weeks the unit shot on location at Truckee in the snow country of the Sierra Nevada. Here Chaplin faithfully recreated the historic image of the prospectors struggling up the Chilkoot Pass. Six hundred extras, many drawn from the vagrants and derelicts of Sacramento, were brought by train, to clamber up the 2300-feet pass dug through the mountain snow.

For the main shooting the unit returned to the Hollywood studio, where a remarkably convincing miniature mountain range was created out of timber (a quarter of a million feet, it was reported), chicken wire, burlap, plaster, salt and flour. The spectacle of this Alaskan snowscape improbably glistening under the baking Californian summer sun drew crowds of sightseers.

In addition, the studio technicians devised exquisite models to produce the special effects which Chaplin demanded, like the miners’ hut which is blown by the tempest to teeter on the edge of a precipice, for one of the cinema’s most sustained sequences of comic suspense. Often it is impossible to detect the shift from model to full-size set.

The Film

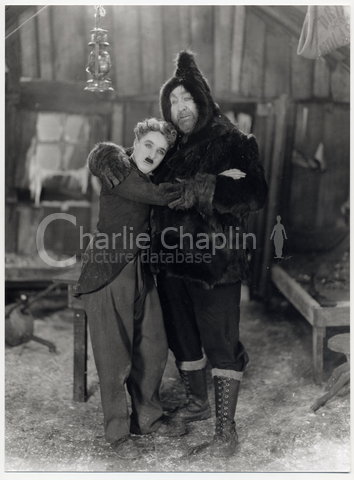

The Gold Rush abounds with now-classic comedy scenes. The historic horrors of the starving 19th century pioneers inspired the sequence in which Charlie and his partner Big Jim (Mack Swain) are snowbound and ravenous. Charlie cooks and eats his boot, with all the airs of a gourmet. In the eyes of the delirious Big Jim, he is transformed into a chicken - a triumph both for the cameramen who had to effect the elaborate trick work entirely in the camera; and for Chaplin who magically becomes a bird. For one shot another actor took a turn in the chicken costume, but it was unusable: no-one else had Chaplin’s gift for metamorphosis.

The lone prospector’s dream of hosting a New Year dinner for the beautiful dance-hall girl provides the opportunity for another famous Chaplin set-piece the dance of the rolls. The gag had been done before, by Chaplin’s one-time co-star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle in The Rough House (1917) ; but Chaplin gives unique personality to the dancing legs created out of forks and rolls. When the film was first shown audiences were so thrilled by the scene that some theatres were obliged to stop the film, roll it back and perform an encore.

The Gold Rush was the first of his silent films which Chaplin revived, with the addition of sound, for new audiences. For the 1942 reissue he composed an orchestral score, and replaced the inter-titles with a commentary which he spoke himself. Among the scenes he trimmed from the film was the lingering final embrace with Georgia, with whom he had maintained a long and often romantic friendship. Perhaps some private and personal feelings caused him to replace the kiss with a more chaste shot of the couple walking off, simply holding hands.

Today, The Gold Rush appears as one of Chaplin’s most perfectly accomplished films. Though he himself was inclined to be changeable in his affections for his own work, to the end of his life he would frequently declare that of all his films, this was the one by which he would most wish to be remembered.

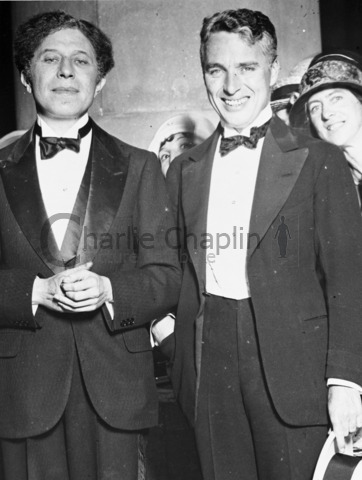

A Memorable Hollywood Premiere

The premiere of The Gold Rush on 26 June 1925 was held in Hollywood’s newest wonder theatre, Grauman’s Egyptian, built three years earlier and - inspired by the recent discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen - decorated in extravagant Ancient Egyptian style. Its proprietor, Sid Grauman, was a friend of Chaplin and had even accompanied The Gold Rush unit on location in the High Sierras. Grauman was famous for the stage shows he mounted as supporting attractions to the films, and determined to create one of his most spectacular for The Gold Rush.

“A Chaplin première,” reported the Los Angeles Evening Herald, “is always an outstanding event…. There was not a vacant seat at the opening. If any ticket-holder preferred to stay away, he could have disposed of his coupons at a fancy figure . . . “

The courtyard in front of Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre was, he continued, “a veritable fairyland of color and light. The most skilled decorators in the realm of make-believe had been at work for a week dressing the enclosure for the occasion.” All Hollywood was there, it seemed; and as each celebrity entered the theatre he or she was announced by a stentorian voice, and each was applauded according to his or her degree of popularity. In the intervals, pretty usherettes served the audience with chilled punch. Each guest was presented with a souvenir programme bound in embossed simulated leather, in which the great names of Hollywood – Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Gloria Swanson, Marion Davies, Buster Keaton, Constance and Norma Talmadge, William Fox, Cecil B. DeMille – had taken pages to congratulate their friend. The stage prologue, said the reporter, was “of matchless beauty . . . Grauman has actually outdone himself in this achievement and The Gold Rush première probably never will be surpassed. If it is, only a genius like Grauman can do it.” The curtain rose on a panorama of the frozen north, revealing a school of seals mounting a jagged crag of ice. The seals were quickly joined by a group of Eskimo dancing girls. This was followed by a recitation of Robert W.Service’s celebrated poem, “The Spell of the Yukon” –

It’s the cussedest land that I know,

From the big, dizzy mountains that screen it

To the deep, deathlike valleys below.

Next came a series of “impressively artistic dances by fascinatingly pretty young women wearing astoundingly rich and beautiful gowns all blending with the Arctic atmosphere and bespeaking the moods of the barren white country.” The numbers which followed included ice skating, a balloon act presented by Miss Lillian Powell and a Monte Carlo dance hall scene.

Only after this long prelude did the audience finally see the film; but the impression it made on them undoubtedly obliterated the memory of Grauman’s stage show. At the end of the film the applause lasted several minutes; and the director-star was led down to the stage. He announced that he was too emotional to make much of a speech – but then characteristically proceeded to deliver a rather good one. Georgia Hale was struck that this was one of the rare occasions when Chaplin had no self-doubts about his work: “He was confident about that. He really felt it was the greatest picture he had made. He was quite satisfied.”

Text by David Robinson / Copyright 2004 MK2 SA