Chaplin as a Composer

Introduction

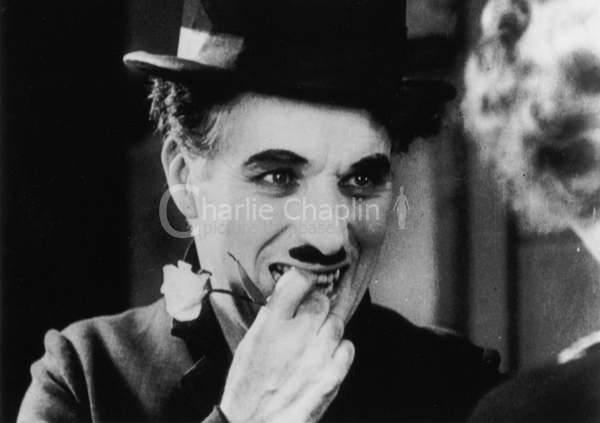

The credit title on City Lights, “Music composed by Charles Chaplin”, brought a surprised and indulgent raising of eyebrows. Because of the occurrence of phrases, here and there, from some familiar melodies, inserted, in most cases, for comic effect, and the use of “La Violetera” (“Who’ll Buy My Violets” by José Padilla) as a theme for the blind flower girl, Chaplin was assumed, by some, to be stretching his claim to everything in the film.

Attitudes changed with the subsequent appearances of Chaplin scores in “Modern Times”, “The Great Dictator”, and “Monsieur Verdoux” (The two latter talkies with occasional musical interludes and “background music”), and with the full score for the reissued “The Gold Rush”. A quality, which can only be described as “Chaplinesque” was discerned and commented upon in this music, despite the fact that it was arranged and orchestrated by other hands.

Those who still believe that Chaplin merely hummed a tune ot two and that “real musicians” did the rest have only to listen to the scores of several of his films. The style is marked and individual. It shows a fondness for romantic waltz hesitations played in very rubato time, lively numbers in two-four time which might be called “promenade themes”, and tangos with a strong beat.

It can now be seen that Chaplin’s music is an integral part of his film conceptions. In similar fashion D.W Griffith also composed some musical themes for his pictures. But perhaps of no other one man can it be said that he wrote, directed, acted, and scored a motion picture.

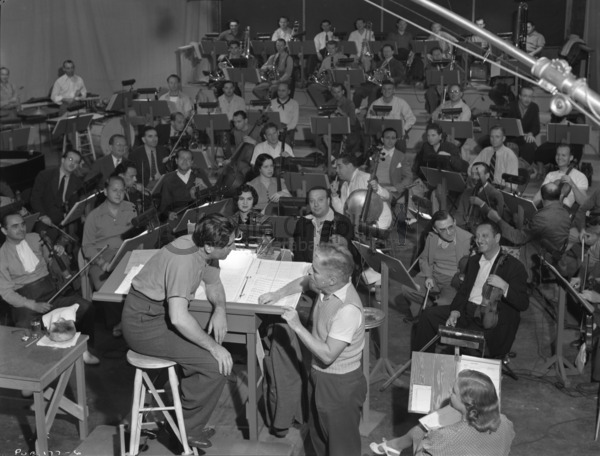

Incidentally, Chaplin even conducted the orchestra, himself, during recordings, an added reason for the satisfying impression of wholeness in the Chaplin films.

Music through his Life

Although musically untrained, Chaplin nevertheless has the advantages of a musical inheritance from his ballad-singer father, the natural endowment of a quick ear, and a superb sense of rhythm, a taste for the art, experience with it on the stage, and an amateur performer’s devotion to it.

In “My Trip Abroad” there is a passage describing his first consciousness of music. As a boy, in Kennington Cross, he was enraptured by a weird duet on clarinet and harmonica, to a tune he later identified as the popular song, “The Honeysuckle and the bee”. “It was played with such feeling that I became conscious, for the first time, of what melody really was”

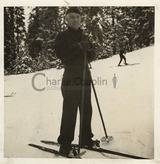

According to Fred Karno’s biography, young Chaplin spent much of his leisure time between shows picking out tunes on an old cello. When Chaplin was signed by the Essanay Company, he bought a violin on which he scraped for hours at night, to the annoyance of less wakeful actors when they all lived next to the studio at Niles, California.

While he was being feted during the negociations with the Mutual Company in New York, Chaplin, appearing at a benefit concert at the old Hippodrome (February 20, 1916), led Sousa’s band in the “Poet and Peasant” overture and his own composition “The Peace Patrol”. That same year Chaplin published two songs “Oh! That Cello” and “There’s Always One You Can’t Forget”, which was a musical tribute to his first romance.

In the twenties he made records of his “Sing a song” and “With you, Dear, in Bombay”, both later used in the sound version of “The Gold Rush”. Subsequent years saw the publication of a theme from “The Great Dictator” to a lyric entitled “Falling Star”, and three numbers from “Monsieur Verdoux” : “A Paris Boulevard”, “Tango Bitterness”, and “Rumba”.

After Chaplin made his first million, he installed a pipe organ in his Beverly Hills mansion. In certain moods he is known to have fingered this expensive instrument for hours at a time. Realizing the importance of musical accompaniment to the silent film, Chaplin sought to have it reproduced in every theatre exactly as he wished it. He supervised the cue sheets (lists of numbers to be played, sent free to all theatres booking a film) of his pictures from “The Kid” (1921) up to “City Lights” (1931) – when it was possible to have the music recorded on the film itself. Then it also was commercially expedient to claim at least “music and sound effects” since by 1931 the silent picture has been superseded by the talkie.

The Music of City Lights

Arthur Johnston and Alfred Newman arranged and orchestrated the music for “City Lights”, Chaplin’s outstanding score. But the melodies, with the exceptions noted above, used for the associations they would evoke, were composed by Chaplin. At least twenty numbers in the score could be published as separate and original works. As was customary in the scoring for silent pictures, the Wagnerian leitmotiv system was followed – a distinctive musical theme associated with which character and idea. The musical cues in “City Lights” come to some ninety-five, not accounting the passages where the music follows or mimics the action in what is generally known as “mickey-mousing” from its use in the scoring of animated cartoons.

A fanfare on trumpets, over a night scene, opens the picture proper. It is heard again as a sort of fate theme at moments of crises, such as the count over Charlie in the boxing ring, and his capture and imprisonment. Saxophone bleating, in slightly off synchronization with the lips, mimics the speakers at the unveiling of the moment. This shrill squeaking is used not only as a comic note itself, but as a burlesque of the talkies. When Charlie is ordered down, a bustling “galop” number in G minorn, played in fast tempo, accompanies his scrambling over the statues. The Tramp’s wanderings through the city streets are accompanied by a gallant bitter-sweet melody mostly on the cello. The theme is repeated seven times when he is in hopeful moods. The flower girl’s principal theme is José Padilla’s “La Violetera”, and phrases of it are played behind the Tramp, when it is pertinent to indicate that his thoughts dwell on her. She had two subsidiary themes, one a pathetique for scenes in her slum room, and the other a violin caprice, for her wistful moments.

The music behind the tramp’s meeting with the eccentric millionaire is an amusing burlesque of opera. A dramatic theme introduces him and is followed by an over-dramatic agitato as he ties the suicide noose. Charlie’s dissuasions are musically rendered in burlesqued opera recitative. Another kind of music is kidded in the accompaniment to Charlie’s promise that “Tomorrow the birds will sing” – the “April-showers, silver-lining, rainbow-round-my-shoulder” sort of “theme song” that echoed through early talkies, particularly in the Al Jolson films. In later sequences the tramp has only to point upward in mock-heroic fashion; no title is necessary, the music “tells” what he is saying.

The nightclub music for the “burning up the town” is a hectic jazz theme with a long sustained high note and marked rhythm. A rumba-like number accompanies the party scene where the tramp swallows the whistle. When the millionaire wakes sober, to find a stranger sharing his bed, there is a snatch of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ballet “Scheherazade” – played in duet form – in low register for the perplexed millionaire and high for the tramp. In like manner bits of “How dry I am”, “I hear you calling me”, etc…are called upon for comic comments.

There are two love themes – one a light romantic waltz played very rubato to action, and a tragic piece associated with the Tramp’s hopeless love. Played also behind the tragic of the picture, with its grim and fateful chords, the second has a distinct Puccini flavor.

A sprightly theme on the bassoon accompanies many of the tramp’s more humorous moments, such as his mishaps behind the streetcleaner’s cart; and there is a singularly amusing use of a tango during the boxing sequence. The fight itself is underlined by a feverish musical “hurry”, also used behind other fast action.

It is true that one or two of the minor numbers are reminiscent. A short dance piece resembles “I want to be happy”. The famous apache dance is a paraphrase. The crooked-fighter theme sounds a bit like “Lock Cut for Jimmy Valentine”. Some Debussy chords herald the morning, and the “Second Hungarian Rhapsody” is cleverly jazzed up for a little chase scene. A film eighty-seven minutes long calls for a score of about a hundred and fifty pages and a little “borrowing” here and there can be overlooked.

“City Lights” ends with the following music. The tramp, let out of prison, searches for the blind girl.

Sequence: Cue 91. Tramp comes to corner where Girl used to sell flowers

Music: “La Violetera” by José Padilla (Played slowly)

Sequence: Cue 92. Tramp wanders the streets…

Music: Tramp Theme (played slowly and tragically)

Sequence: Cue 93. Tramp finds flowers in gutter…

Music: “La Violetera” by José Padilla (normal tempo)

Sequence: Cue 94. He turns to the girl in the window of her shop laughing at him…

Music: Violin Caprice (secondary girl theme)

Sequence: Cue 95. Girl touches hand of tramp…

Music: Tragic love theme

Incidentally, sound effects are sparingly used, and then only for deliberately pointed effects, like the swallowed whistly, bells, the firing of revolvers etc… Falls and blows are not accented by traps, nor are there the other tasteless noises by ratchets, etc…that have featured so many “revivals with sound added”, copies from the distracting technique of sound cartoons. Above all, the human voice is not employed, an artistic mistake too often made in attempts to bring old silent pictures “up to date”.

The haunting and pleasant Chaplin melodies in “City Lights” are pleasing in themselves, but the picture is one of the few extant examples of the silent medium’s power when wedded to a musical score which properly interprets the action and heightens the emotion. The legend has grown that silent pictures were accompanied by a thinkling piano, either played thumpily in the so-called “nickelodeon” manner, or in a more dignified, but essentially neutral style. Actually, from 1914 on, every town of five thousand or over had at least a three-piece orchestra – or an organ. The Griffith and Fairbanks films, specials like “The Covered Wagon” and “The Big parade”, all had orchestras travelling with them, playing scores as carefully worked out as “City Lights”.

By strict musical standards Chaplin’s score may not equal those of Virgil Thompson, Max Steiner, Georges Auric or William Walton. Thompson’s scoring for “The River” and “Louisiana Story”, with extremely clever arrangements of old folk tunes, is far more sophisticated and intellectual. Nor does Chaplin possess the virtuosity and present grandiose manner of Steiner, where too often sheer bombast attempts to make up for the emotional vacuity in the picture itself. But who, better than Chaplin, could point up musically the tragic-comic adventures of the tramp character he himself created ?

Extract from « Charlie Chaplin » by Theodore Huff, published by Henry Schuman Inc., New York 1951. Chapter XXV, Chaplin as a Composer