Essanay - Chaplin Brand

By Jeffrey Vance, adapted from his book Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema (New York, 2003) © 2009 Roy Export SAS

If the early slapstick of the Keystone comedies represents Chaplin’s cinematic infancy, the films he made for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company are his adolescence. The Essanays find Chaplin in transition, taking greater time and care with each film, experimenting with new ideas, and adding flesh to the Tramp character that would become his legacy. Chaplin’s Essanay comedies reveal an artist experimenting with his palette and finding his craft.

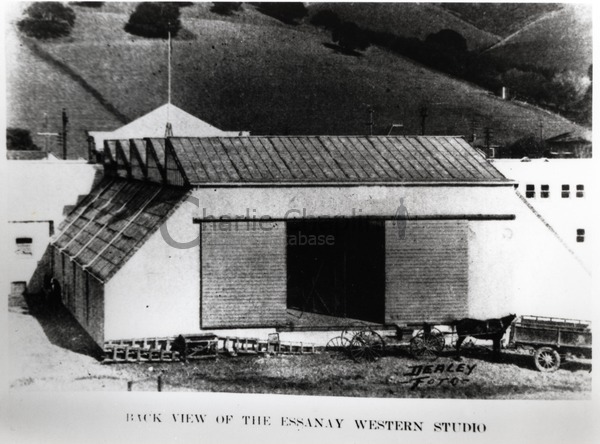

After the expiration of his one-year contract with the Keystone Film Company, Chaplin was lured to Essanay for the unprecedented salary of $1,250 per week, with a bonus of $10,000 for merely signing with the company. The fourteen films he made for the company were distinctly marked and designated upon release as the “Essanay-Chaplin Brand.” The company’s headquarters were in Chicago, Illinois, and the company had a second studio in Niles, California. The name Essanay was formed from the surname initials, S and A, of its two founders: George K. Spoor, who provided the financing and managed the company, and G.M. Anderson, better known as “Broncho Billy” Anderson, cinema’s first cowboy star.

Essanay began in 1907 and a year later became a member of the powerful Motion Picture Patents Company. Chaplin’s one year with the company was its zenith. The studio foundered after Chaplin left to join the Mutual Film Corporation and finally ceased operations in 1918. Essanay would most likely be largely forgotten were it not for Chaplin’s early association.

While no single Chaplin film for Essanay displays the aggregate transformation to the more complex, subtle filmmaking that characterizes his later work, these comedies contain a collection of wonderful, revelatory moments, foreshadowing the pathos (The Tramp), comedic transposition (A Night Out), fantasy (A Night Out), gag humor (The Champion), and irony (Police), of the mature Chaplin films to come.

The most celebrated of the Essanay comedies, The Tramp is regarded as the first classic Chaplin film. It is noteworthy because of Chaplin’s use of pathos in situations designed to evoke pity or compassion toward the characters, particularly the Tramp. An innovation in comedic filmmaking, The Tramp dares to have a sad ending. Pathos also appears in The Bank, in which Charlie’s heart is broken when the object of his affection throws away the flowers he has given her and tears up the accompanying love note.

Chaplin infuses the Essanay comedies with a number of other innovations. The first is comic transposition. In A Night Out, his second film for Essanay, the Tramp, thoroughly inebriated, gently puts his cane to bed, “pours” himself a glass of water out of a candlestick telephone, and uses toothpaste to polish his boots. Chaplin also employs fantasy for the first time in the Essanays films. In A Night Out, as Ben Turpin pulls the Tramp along the sidewalk, he believes that he is floating among flowers on a river. Chaplin’s own style of gag comedy develops in the Essanays, exemplified in The Champion, in which a David-like Tramp receives the assistance of his loyal bulldog to best his Goliath-like boxing opponent. Irony, a hallmark of Chaplin’s mature work, appears for the first time in the Essanays. Irony is conspicuous in Police, in which an evangelist implores the Tramp (who has just been released from jail) “to go straight” but is later revealed to be a pickpocket himself. Finally, Chaplin first utilizes several other devices in the Essanay comedies that will become signature features of his later films: dance (Shanghaied), the equivocal ending (The Bank), and the classic Chaplin fade-out (The Tramp).

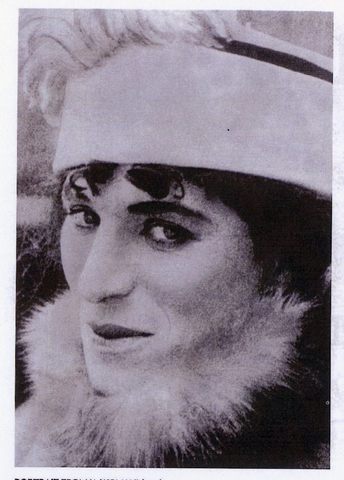

Nowhere is the evidence of Chaplin’s growing cinematic maturity more evident than in the subtle evolution of the Tramp’s treatment of women in the Essanay comedies. At Essanay, Chaplin found Edna Purviance, who would remain his leading lady until A Woman of Paris (1923). Born Olga Edna Purviance in Nevada in 1895, she had trained as a secretary and was recommended to Chaplin by an Essanay employee as a beautiful young woman who frequented a popular San Francisco café. Chaplin was instantly captivated by her beauty and charm. The personal chemistry between Chaplin and Purviance served the Tramp’s changing attitudes toward women well, resulting in no small part from the intimate relationship the two enjoyed off screen. In the Keystone comedies, the Tramp was usually at odds with the women in his life, such as his frequent foil Mabel Normand. Purviance was far more demure and refined, and the Tramp’s interplay with her is gentle and often romantic. Although the female characters of the first Essanays are indistinguishable from those of the Keystones (more often than not, objects of desire, derision, or simply unimportant to the plot), beginning with The Champion, there is a softening in the Tramp’s attitude toward women. The romantic longing at the beginning of A Jitney Elopement demonstrates this transformation.

The evolution of the Tramp was undoubtedly fueled by Chaplin’s efforts to seize greater creative control over his films. Unlike the Keystone comedies, which have simple plot and place a primacy on farce humor, Chaplin’s Essanay comedies display more sophisticated plots and involve more textured characters. The maddening pace of producing nearly one new Keystone comedy each week was reflected in the rapid pace and formulaic story lines in the films. However, the pace at Essanay was somewhat slower, allowing Chaplin to take more time and care in creating his films, and more room to experiment. The tempered pace shows in the style of the films, which contain more subtle pantomime and character development. Although the first seven films Chaplin made for Essanay were released over three months, Chaplin slowed the pace of production to one two-reel film per month after that.

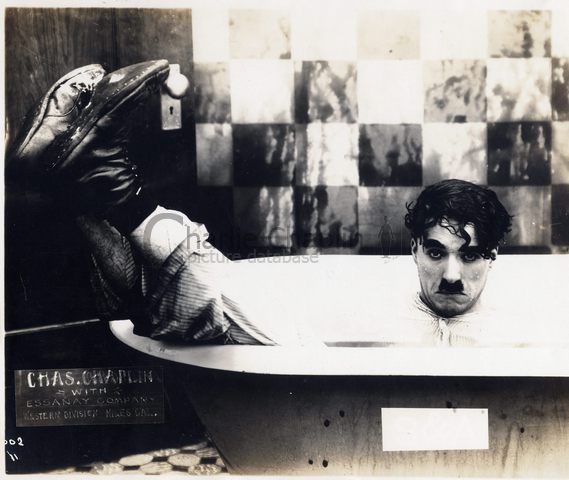

Chaplin also wanted to gentrify his films, being very much aware of criticisms that attacked his earlier work as vulgar and crude. More refined comedy was familiar territory for Chaplin, who learned his art in the British music halls, where bringing an audience along as character and story were developed was paramount to getting the big laugh. The great French silent-film comedian Max Linder, whom Chaplin admired, pioneered this method of acting in film. The Tramp’s drunken mannerisms in A Night Out and A Night in the Show borrow heavily from Chaplin’s classic music-hall acts, and his female impersonation in A Woman reflects the style of masquerade comedy found in many music-hall sketches.

Chaplin’s early efforts to pull Essanay in the direction of character-based comedy brought about a certain degree of tension with his employer. After all, the name of the company was the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, and a factory culture prevailed there. Standardization was actually a goal of the Motion Picture Patents Company, in which Essanay had been participating for seven years by the time Chaplin joined it. Its position in the film industry had been won by series films such as the Broncho Billys, the Alkali Ikes, the Snakevilles, and the George Ade Fables. No doubt its expectation was that Chaplin would provide another successful, if predictable, run of more-or-less standardized product. Alarmed when he was instructed at Essanay’s Chicago studio to pick up his script from Essanay’s head scenario writer, Louella Parsons (who later became a powerful Hollywood gossip columnist), Chaplin snapped, “I don’t use other people’s scripts, I write my own.” (1)

Chaplin had other disagreements with Essanay from the beginning. The company’s co-founder, George K. Spoor, had never heard of Chaplin and was reluctant at first to give him his promised $10,000 signing bonus. Chaplin also refused to allow Essanay’s practice of projecting the original negative when screening rough film footage, which saved the studio the expense of making a positive copy, insisting that viewing prints had to be made. After Chaplin left Essanay, he despised the company’s unscrupulous tactics of re-editing his films using discarded material in various forms. It was perhaps because of this acrimony (and the resulting lawsuits) that Chaplin remained bitter about this period in his career for the rest of his life.

Chaplin’s dismissive treatment of the comedies he created for Essanay is unfortunate. Apart from their revelation of the fascinating and subtle evolution of Chaplin’s comedy, these films demand a prominent place in the history of film for another, simpler reason—they made Chaplin an icon. Adorned with his instantly recognizable makeup, Chaplin became the most famous man in the world when worked for Essanay in 1915. An article in Motion Picture Magazine stated, “The world has Chaplinitis…Any form of expressing Chaplin is what the public wants…Once in every century or so a man is born who is able to color and influence the world…a little Englishman, quiet, unassuming, but surcharged with dynamite is flinching the world right now.” (2)

Essanay exploited Chaplin’s success to the hilt. The Tramp was the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics, spawning songs as well as toys, postcards, cartoon strips, and statuettes that bore his likeness. Imitation, the sincerest form of flattery, was often upon the Tramp in this period as well, as a host of imitators appeared—from Billie Ritchie to Harold Lloyd’s early Lonesome Luke character.

Chaplin’s Essanay comedies hold another distinction. For the first time in his career, words that would be applied to Chaplin for the rest of his life—comic artistry and genius—were written in praise of his work. Indeed, there are moments in these early films that deserve such accolades. Perhaps the greatest joy in watching them is the discovery of many conceits, themes, and devices that would serve the great clown so well in the creation of his mature films.

Not Mentioned in the Filmography Section

His Regeneration (Released: May 7, 1915)

Chaplin made a guest appearance in this one-reel G.M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson drama, as the Tramp in the film’s dance-hall sequence. That the main title states that Anderson was “slightly assisted by Charles Chaplin” suggests that Chaplin may have had a hand in the construction and direction of the film as well. The plot of the drama bears a close resemblance to the story used in Chaplin’s Police.

Triple Trouble (Released: August 11, 1918)

This film, which Essanay claimed was a “new” Chaplin comedy, was released nearly three years after the conclusion of Chaplin’s contract with the company. The film was assembled from the discarded portions of Police, the ending of Work, and an abandoned feature-length production entitled Life, along with some new footage directed by Leo White in 1918. The plot has Charlie working in the home of an eccentric inventor from whom some German spies are attempting to obtain a formula. Triple Trouble, however, is best seen as an opportunity to view portions of the abandoned Life, Chaplin’s first attempt to direct himself in a feature-length film, and the doss-house sequence intended for Police.

Endnotes

1. Chaplin, My Autobiography (London, 1964), p. 176

2. Charles J. McGuirk, “Chaplinitis,” Motion Picture Magazine, 9 no 6 (July 1915): 121-124.

3. Chaplin, My Autobiography, 186.