A Woman of Paris Music

Article about the creation of a new score for A Woman of Paris by composer/conductor Timothy Brock. The score is currently available for live orchestral screenings of the film.

The dilemma of the 1977 version of the score to A Woman of Paris is a complex one, and for me, a source of mixed feelings. On behalf of the Chaplin estate, and of behalf of the composer himself, the primary objective has always been to restore the Chaplin scores as close (as I can come) to how Chaplin would have heard them himself. In the case of Modern Times, it was a painstaking 14 months of solid meticulous work, and City Lights and The Circus: being much the same. However for A Woman of Paris my 8th score restoration for the Chaplins, the goal was the same, but more than few educated guesses and well-thought-out liberties had to be taken. This was a very different kind of restoration.

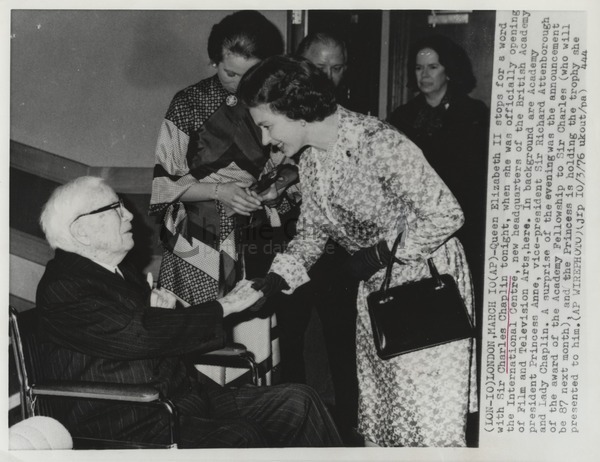

When preparations for the re-release of A Woman of Paris were being made in 1976, Chaplin’s health was in full decline. He had had a stroke and it was only with great effort he had managed to complete the work required of him. Like the other re-issues up to this time, The Circus, The Kid, Sunnyside, Pay Day, The Idle Class and A Day’s Pleasure, Chaplin had composed music (with the assistance of Eric James) for them all. 226 minutes of fully orchestrated scores in 6 years time, from the composer’s age of 81 to 87. But for A Woman of Paris the last film to be re-released, Chaplin’s health had deteriorated rather significantly, and due to the efforts of James and others, a “Chaplin” score had been created by means of using some previously un-used compositions and by James’ emulation of the Chaplin style, which he knew well after some 18 years of working with him.

The 1977 score suffers primarily from one simple fact: the lack of material. One can only speculate that James, not wanting to “ghost write” a score in the name of Chaplin, used what little he had been given by Chaplin at age 87, and therefore tried to stretch the material over the course of 82 minutes. Moreover the available un-heard compositions that James brought out were originally written for comedies, and were most likely difficult to convert to dramatic situations. Equally the orchestration by Eric Rogers, perhaps not as familiar with the Chaplin technique as Eric James , did not follow the stylistic guidelines established by previously published trademark-Chaplin scores.

All of these understandable reasons, among others, were contributing factors to a not-all-together successful score. And although dozens of festivals over the last 30 years had expressed desire to exhibit A Woman of Paris many were reluctant. However, as it holds true for all Chaplin films, one must abide by the credo that testifies to the complete art that is a Chaplin film. It must be his music and nobody else.

Enter 2003. The Association Chaplin transferred to CD for preservation a series of over 19 hours of miraculous home and studio recordings. Dating back as early as 1951, these recordings are of Chaplin composing music on the piano, which he subsequently gave to his musical associates later to transcribe onto paper. A large portion of these recordings are devoted to music he was composing for Limelight (however one can hear the budding musical themes of not only Limelight but also later recordings he made composing The Kid, The Pilgrim and The Circus.

The music Chaplin composed here, in the year 1951, is really the young composer at work, and these amazing recordings reflect that creative energy and vitality in his music that somehow always come through in his films. Yet Chaplin had composed so much music for Limelight that, due to one reason or another, much of it had been left out of the final cut. And along with Modern Times, The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux there are stacks of rejected musical material from Limelight in the archives in Montreux. But, curiously, almost none of the unused portions of Limelight on these recordings exist anywhere on paper. So from these early recordings, I established and transcribed the “unknown” compositions onto paper, totaling about 14 complete compositions, and 20 or more incomplete or nearly complete ones.

This, perhaps, was the answer. Music written while he was still at the peak of his composing abilities, music for his ONLY other serious dramatic feature, and music completely un-heard by the public before.

So in co-operation with the Chaplin family, I carefully proceeded to create a new score for A Woman of Paris by using both the recently un-earthed exciting compositions of 1951, and reconfiguring some of the existing themes from the 1977 score, but more in the manner of previous Chaplin treatments of his own material. The orchestration model I used was an exact duplication of the forces for City Lights: flute (piccolo), oboe (cor anglais), 3 clarinets, 3 saxophones, bassoon, 2 horns, 3 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, percussion, harp, piano (celesta) and strings, with the exception of the banjo, but with the addition of accordion (as in The Pilgrim).

This experiment, I earnestly hope, will prove a worthy companion to A Woman of Paris which has for so long gone without proper musical support. Although Chaplin could not have foreseen the difficulty which arose from the score during the last year of his life, I do hope it would be to his liking if he were here today. After all, that has always been the ultimate goal.