Filming City Lights

City Lights proved to be the hardest and longest undertaking of Chaplin’s career. By the time it was completed he had spent two years and eight months on the work, with almost 190 days of actual shooting.

The marvel is that the finished film betrays nothing of this effort and anxiety. As the critic Alistair Cooke wrote, the film, despite all the struggles, “flows as easily as water over pebbles”.

As usual with Chaplin’s projects, the story went through many changes. From the start he decided it would be about blindness. His first idea was that he himself should play a clown who loses his sight but tries to conceal his handicap from his little daughter.

From this he moved to the idea of a blind girl, who builds up a romanticised image of the little man who falls in love with her and makes great sacrifices to find money for her cure.

Once this was decided, he had - unusually - a clear idea of how the film would end - the moment when the blind girl, her sight restored, finally sees the sad reality of her benefactor. Even before he shot it, he had a sense that if it succeeded this would be one of his finest scenes.

He was right. The critic James Agee said that it was “the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies”.

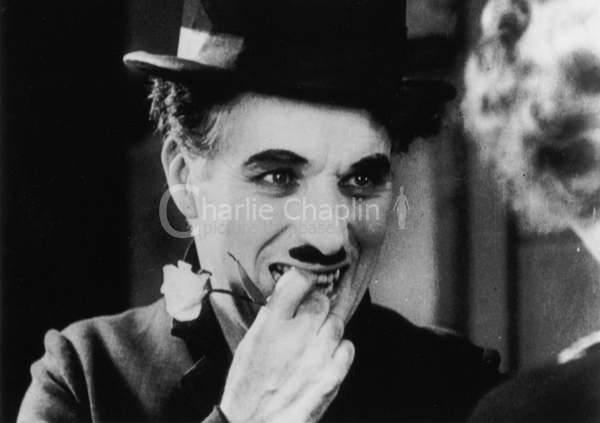

Near the end of his life, Chaplin still marvelled at the magic of the scene: “I’ve had that once or twice, he said, …in City Lights just the last scene … I’m not acting …. Almost apologetic, standing outside myself and looking … It’s a beautiful scene, beautiful, and because it isn’t over-acted.”

He spent many laborious weeks on the deceptively simple scene where the Tramp and the flower girl first meet, setting up the premise of the story. Here, in two or three minutes, through action alone, he establishes the meeting of the two people; the Tramp’s recognition that she is blind, and his instant fascination and pity and the girl’s misconception that this poor creature is a rich man. At the end of the sequence, having built up the sentiment to a high pitch, he brilliantly dashes it with a touch of broad comedy.

“It is completely dancing,” said Chaplin. “It took a long time. We took this day after day”.

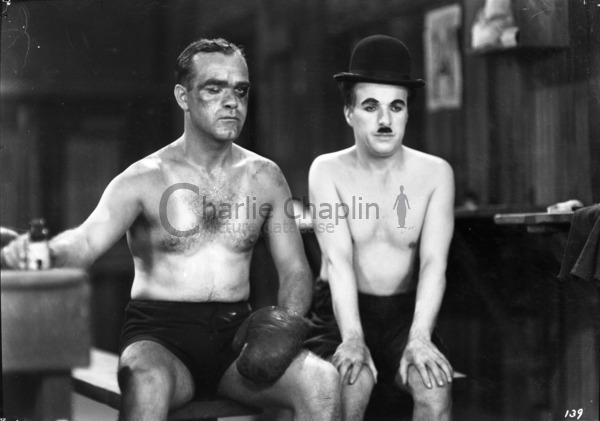

To play the blind girl he chose a 20-year-old Chicago socialite and recent divorcée, Virginia Cherrill. Inexperience was never a disadvantage in Chaplin’s eyes - he just wanted actors who would obediently follow his instruction. He was impressed by her ability to give the impression of blindness. To achieve it he advised her, in his own words “to look inwardly and not to see me.”

Their collaboration was not easy. Virginia was the only actress with whom Chaplin failed to establish personal sympathy. More than 50 years later, Miss Cherrill declared, “Charlie never liked me and I never liked Charlie”

For his part, he felt she lacked the necessary dedication to the job - “she was an amateur”, he said scornfully. On one occasion he even tried to replace her with Georgia Hale, who had been his leading lady in “The Gold Rush.” Yet despite - or perhaps because of - the struggles, the performance he finally won from her is as near as may be perfect.

However severe Chaplin was with others, he was always even harder on himself. In this case he had the strength of will to cut out a scene which he know was brilliant, but which simply did not fit into the finished film. It is a polished set of variations built about the simplest idea. The Tramp simply spies a piece of wood stuck in a grating, and idly tries to free it. No more - yet the Tramp’s concentration, and the curiosity he arouses in passers-by was transformed into a sequence of high comedy.

Even before he began City Lights the sound film was firmly established. This new revolution was a bigger challenge to Chaplin than to other silent stars. His Tramp character was universal. His mime was understood in every part of the world. But if the Tramp now began to speak in English, that world-wide audience would instantly shrink. Moreover there was the problem of how he should talk. Everyone, across the world, had formed his or her own fantasy of the Tramp’s voice. How could he now impose a single, monolingual voice?

Chaplin boldly solved the problem by ignoring speech, and making City Lights in the way he had always worked before, as a silent film. His only concessions were to add a synchronised musical score; and to introduce one or two sound effects - like the disconcerting chirruping of a whistle he has swallowed - which showed that he could use sound as creatively as images for comedy purposes. Already with his silent features he had paid great attention to the music played by live orchestra for the first runs of his feature films. Now he astounded the press and the public by composing the entire score for City Lights

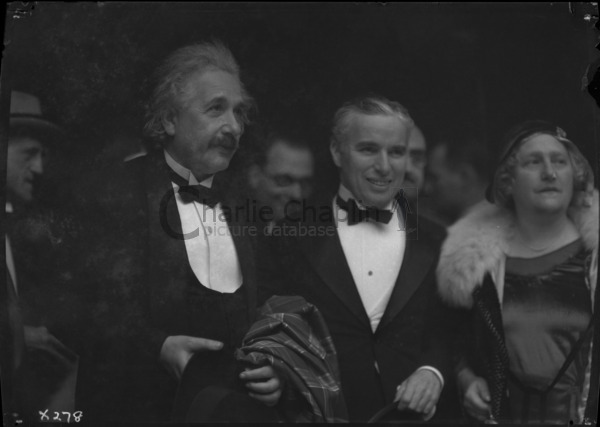

The premieres were among the most brilliant the cinema had ever seen. In Los Angeles, Chaplin’s guest was Albert Einstein; while in London Bernard Shaw sat beside him. City Lights was a critical triumph. All Chaplin’s struggles and anxieties, it seemed, were compensated by the film which still appears as the zenith of his achievement and reputation.

Text by David Robinson / Copyright 2004 MK2 SA